How might we design a safer, more inclusive, San Franscisco for its most marginalized

and at-risk populations?

Before the opioid epidemic was declared a national public health emergency and drug overdoses became the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50, I was working alongside a cultural anthropologist, harm reduction activists, and S.F.'s wider drug-users rights community to imagine alternative futures where dangerous and fatal 'on the run' drug use no longer existed.

Challenges faced were multi-fold: (1) gaining the trust of a community who viewed me as an outsider, (2) working on culturally and politically divisive issues, and (3) supporting a newly formed organization lacking a singular mission.

Outcomes included a series of speculative design workshops where drug users imagined what a public health intervention—a safe injection site (SIS)—would look like if it existed in the Tenderloin district. A flyer project that brought members of an organization together, and engaged the city's homeless residents in idea generation on the future of urban public spaces.

Partners: S.F. Urban Survivors Union (USU) + S.F. Aids Foundation

Role: designer + researcher working with a cultural anthropologist

Extent of the project: four years, volunteer basis

Recognition: published in the book “Streetopia in the Tenderloin” (2015), exhibited at “STREETOPIA” in SF (2012), SF Weekly (2012)

Tags: ethnographic research, community-driven design, speculative design, participatory design, co-creation

Design Process.

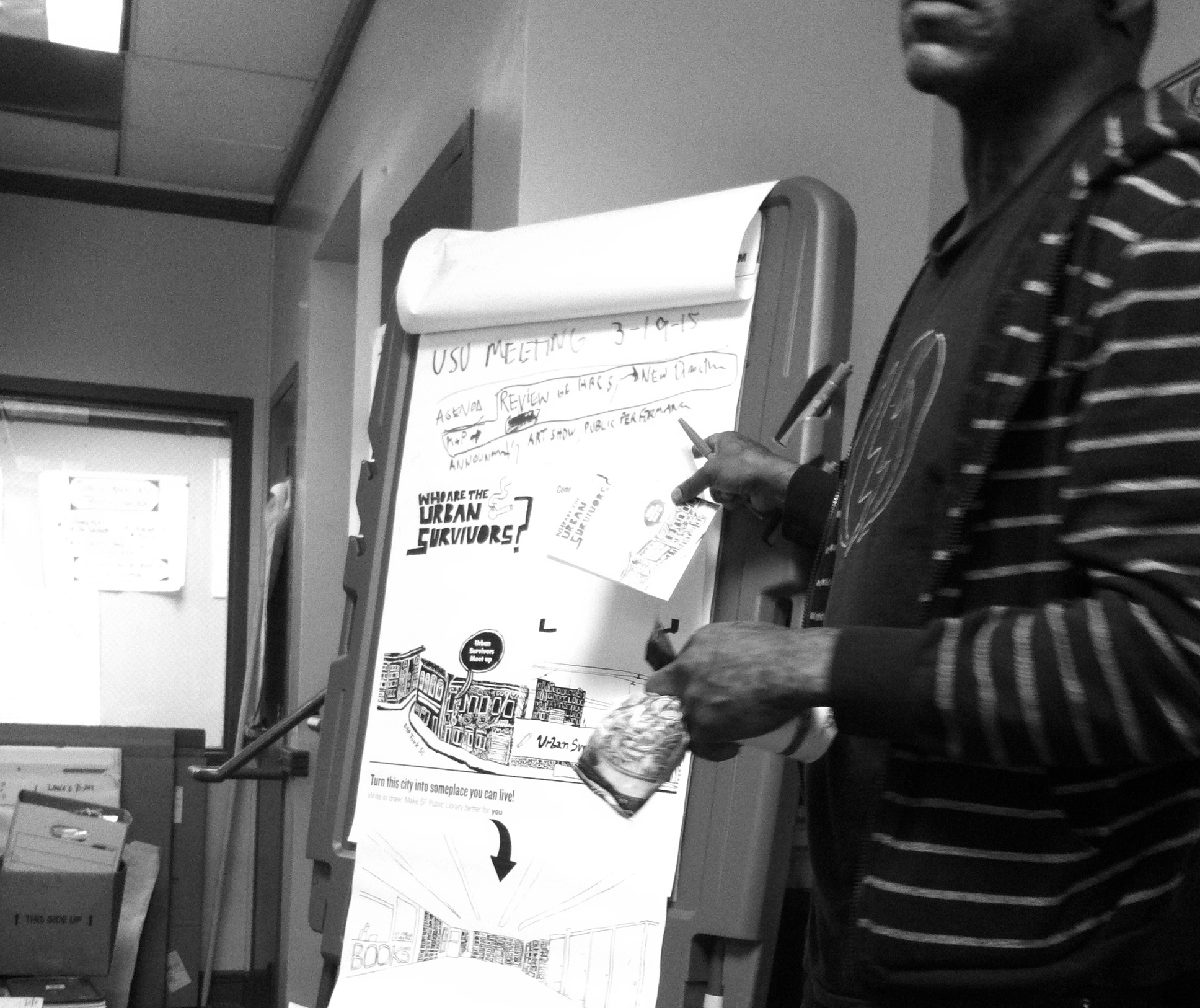

I spent a lot of time in the beginning building rapport with members of the Urban Survivors Union. I not only attended meetings, but also led speculative design workshops and engaged them in the design process.

Phase I: Who are the Urban Survivors?

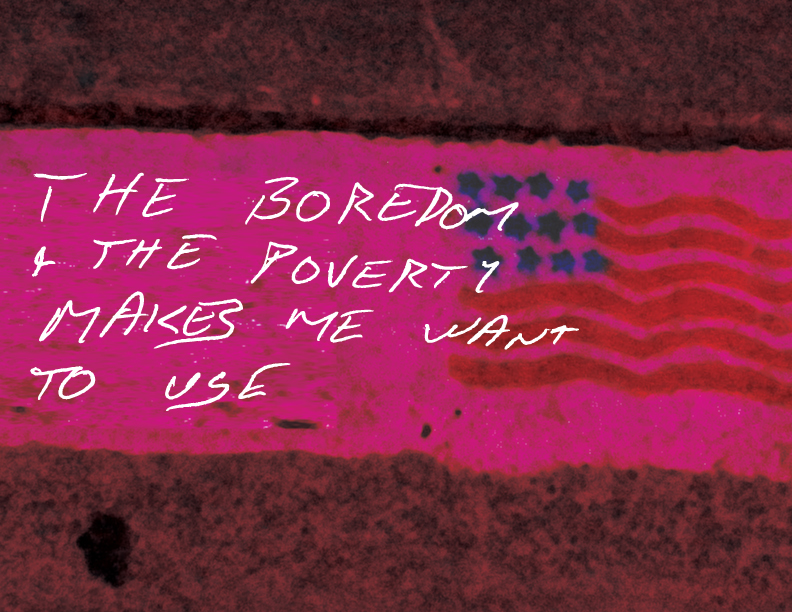

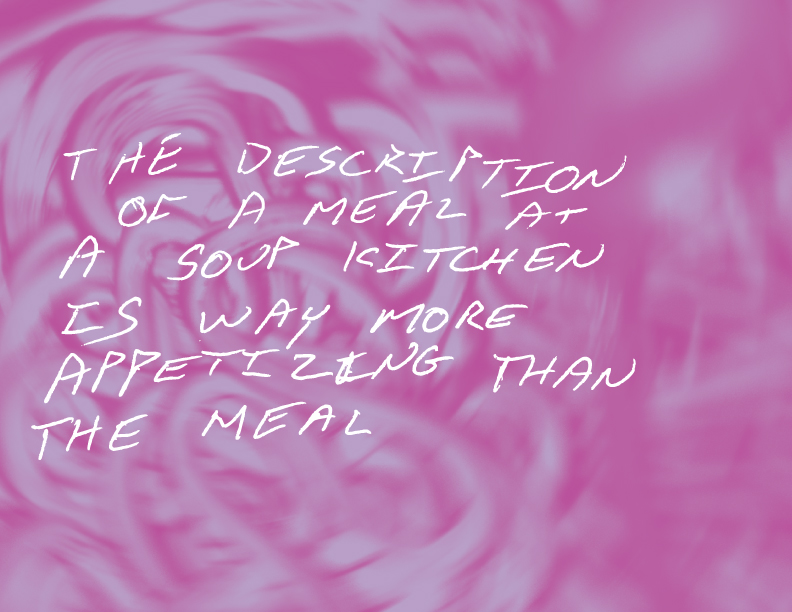

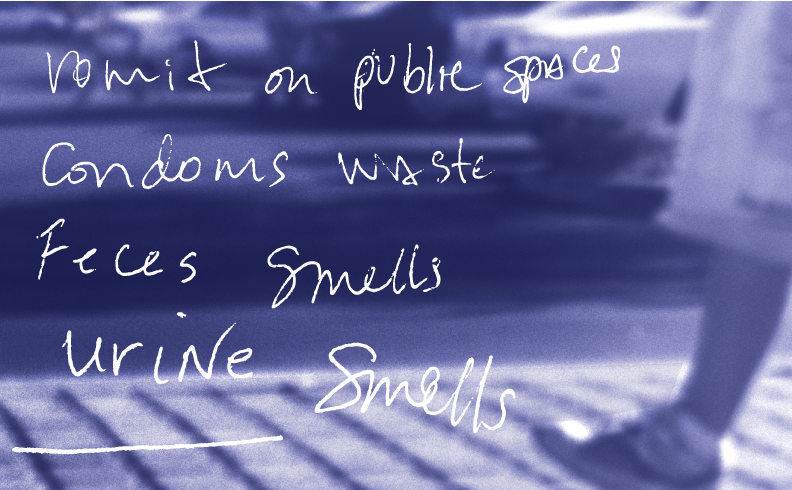

To better understand the drug user community, I began by conducting speculative design workshops with mutually beneficial goals—uncovering needs, values, and motivations of individuals being served by the USU.

One workshop asked members to write narratives of a day in the life of an urban survivor. Examining these narratives, we generated ideas for interventions that could have helped address the pain points mentioned by participants. Ideas from these workshop led interventions shown in next Phases, and a partnership with the S.F. AIDS Foundation where we charted the past and the future of needle exchanges.

The members spoke throughout the design process about how they wished to be understood as a community—a group of people grappling with urban life and illness. Many understood their drug use as 1) a way of managing underlying psychiatric illnesses & physical pain, and 2) a way of life that does not present itself as a choice between drugged & drug-free living.

Some key themes emergerd the led to the design on the next Phases:

- Desiring to have community and be seen as a community

- Wanting public spaces to feel safe and showcase care

- Experiencing boredum, lonliness, and lacking avenues for self expression

- Vewining drug use not as a disease, but as a way of life

Notecards from an exercise where USU members described worst experiences during their day, and imagined interventions they wished they had during the those moments.

In partnership with the S.F. AIDS Foundation—harm reduction activists, community members, and needle exchange users—charted the history of the needle exchange as they experienced it in their lifetime, and imagined what a future exchange network could be.

Phase II: Safe Injection Site (SIS)

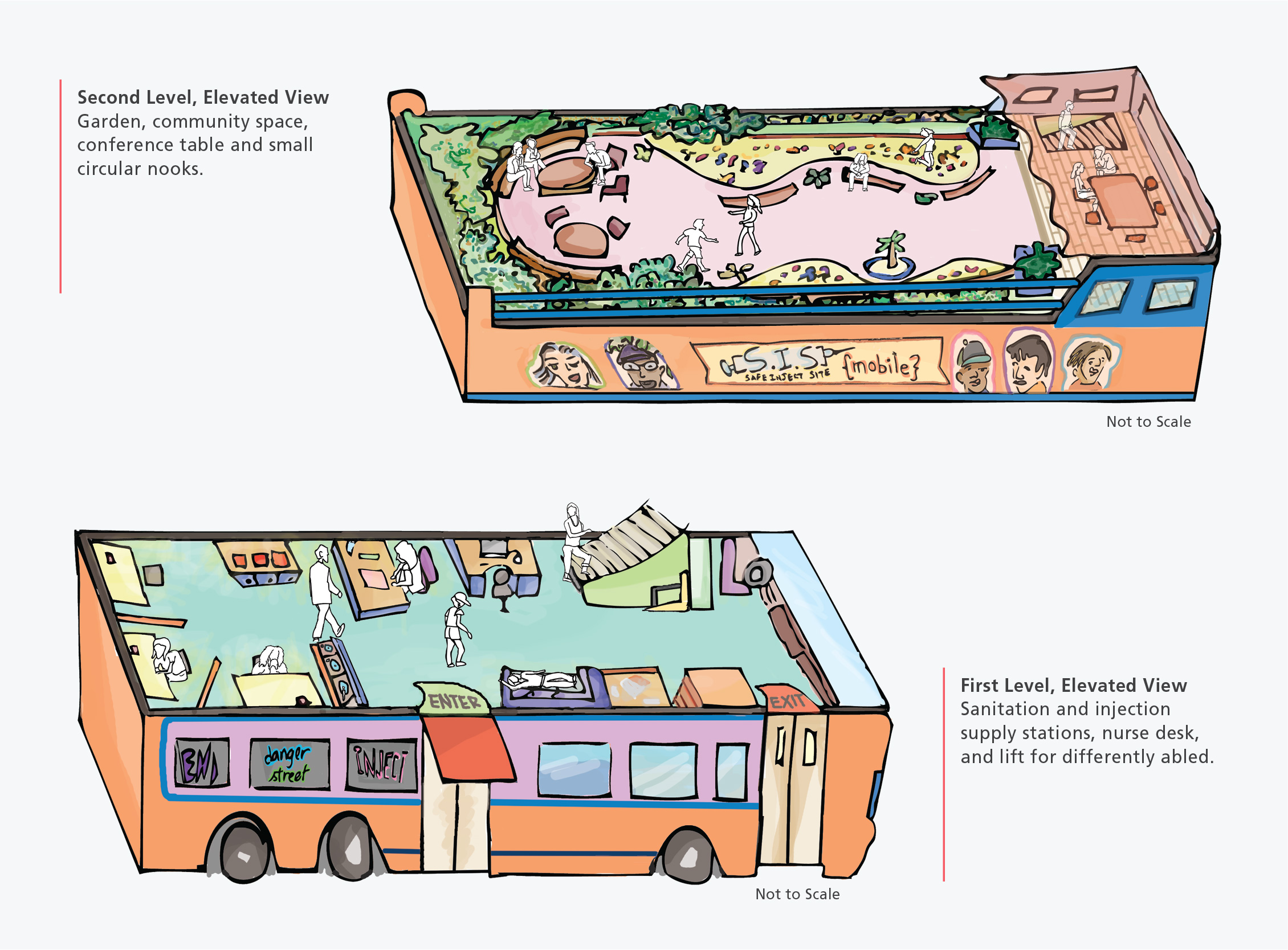

The idea for a mobile SIS came up in a workshop when a community member spoke about the fact that there are more overdose events in S.F. than even car accident deaths. SIS's are places where drug users can inject in a safer way with supervision, support, and counseling.

Many medical and public health communities support SIS's, which are an emerging priority in North American cities and a matter of life and death for those at risk of

infection and overdose death from rushed, dirty, unlighted, and unsupervised street

injecting. Working with mood boards, slogans developed during workshops, and constant feedback from the community, I rendered a mobile SIS, as a refurbished double-decker bus with first level injection booths and second level open-air community space addresses drug users’ visions of a flexibly-sited caring space.

I chose to make the rendering look imaginative because SIS's are usually depicted as sterile clinical spaces; community members wanted to depict a space that would spark conversation about possibilities.

One of the main reasons SIS’s aren’t built, even though medical evidence shows their health benefits: NIMBY-ism (‘not in my backyard-ism’) makes it politically difficult to site an SIS. A mobile SIS unit avoids this problem, while giving more clients access. The bus can be located anywhere and can follow a fixed or flexible route—reaching those in need wherever they are.

Phase III: Urban Survivors Union (USU) Flyer Project

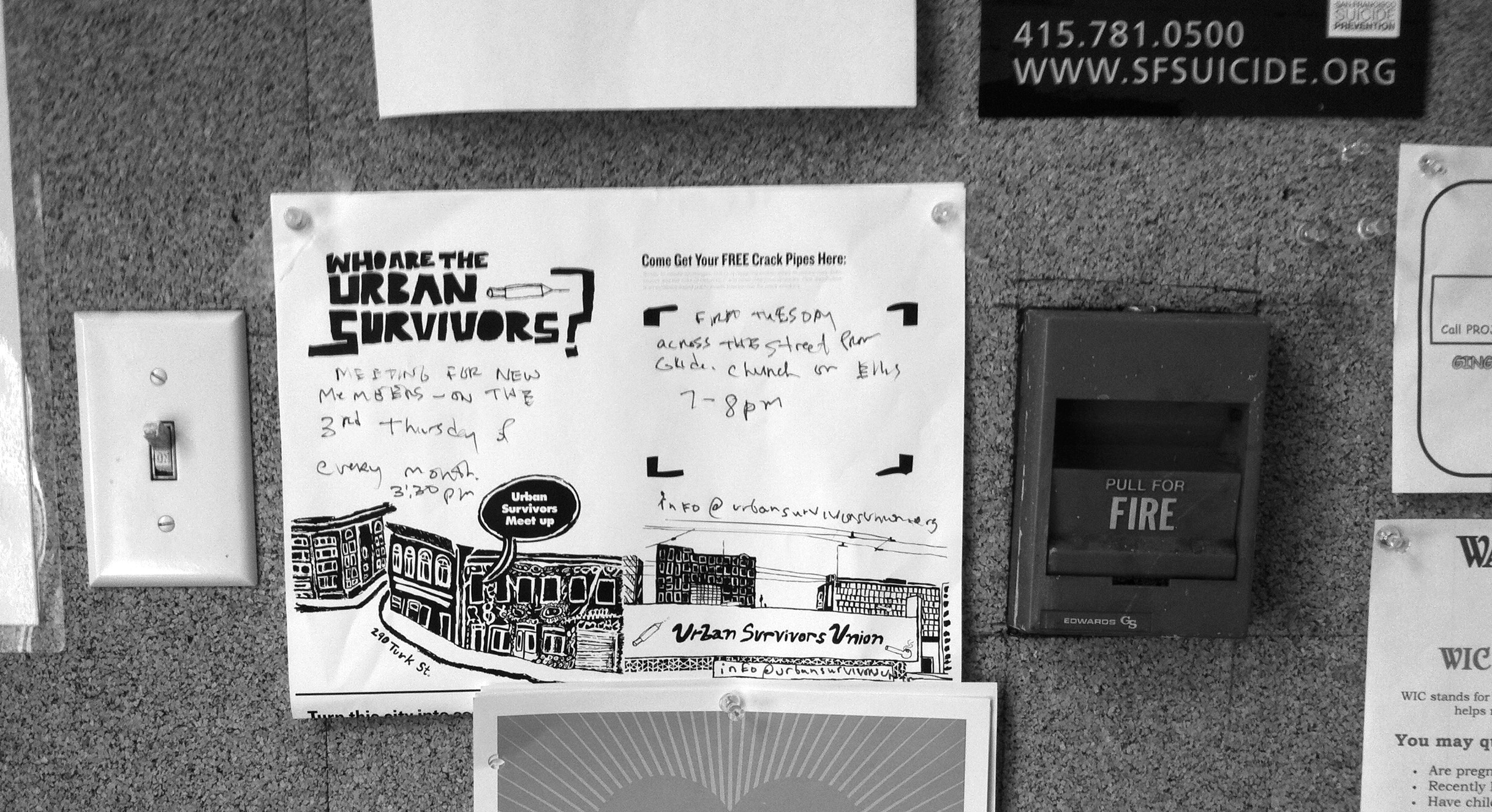

Being a designer, I was asked to design a flyer for a pipe distribution program run by the USU. I took it as an opportunity to build a shared activity for organizational members & engage their users in speculative design.

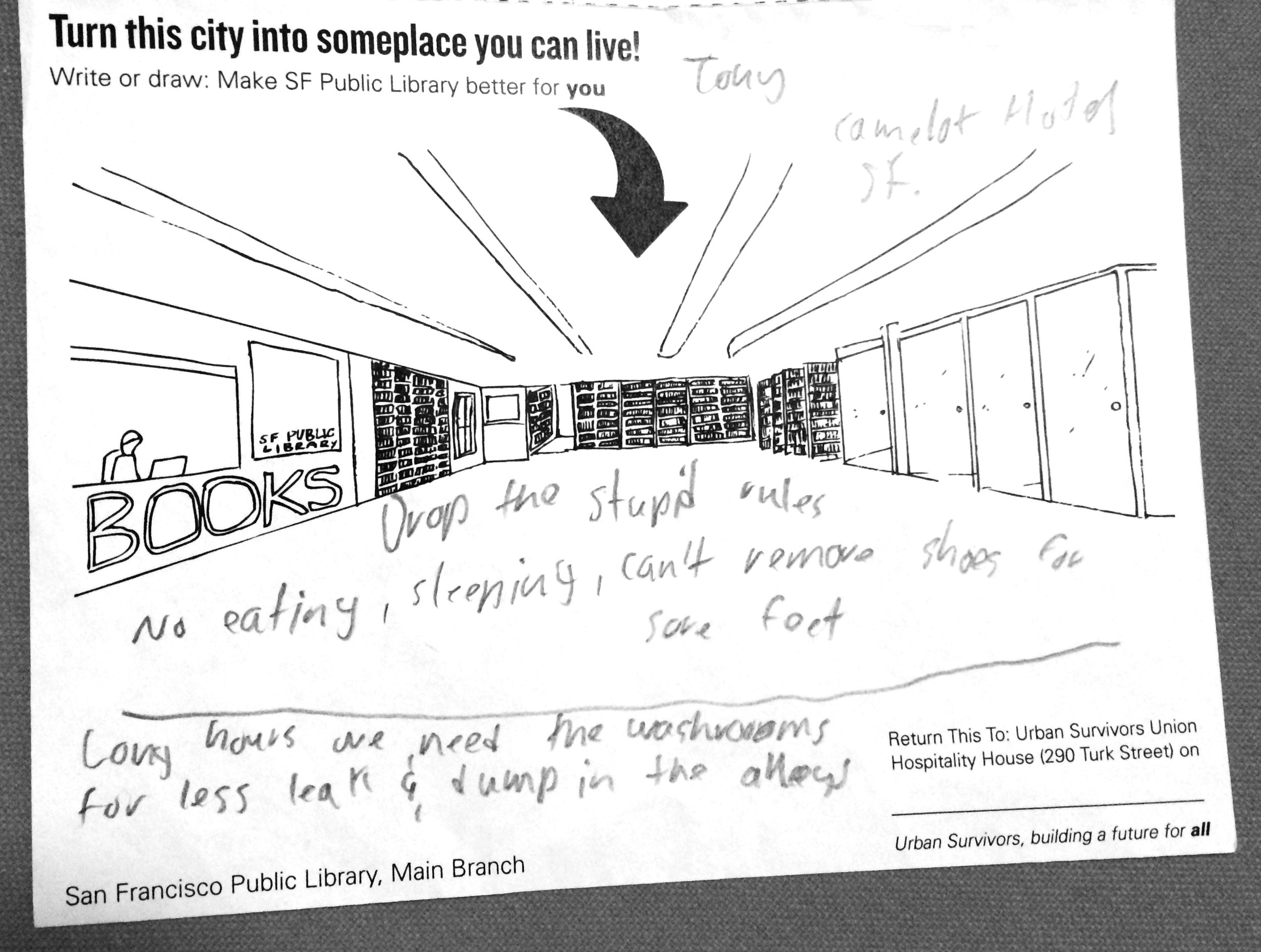

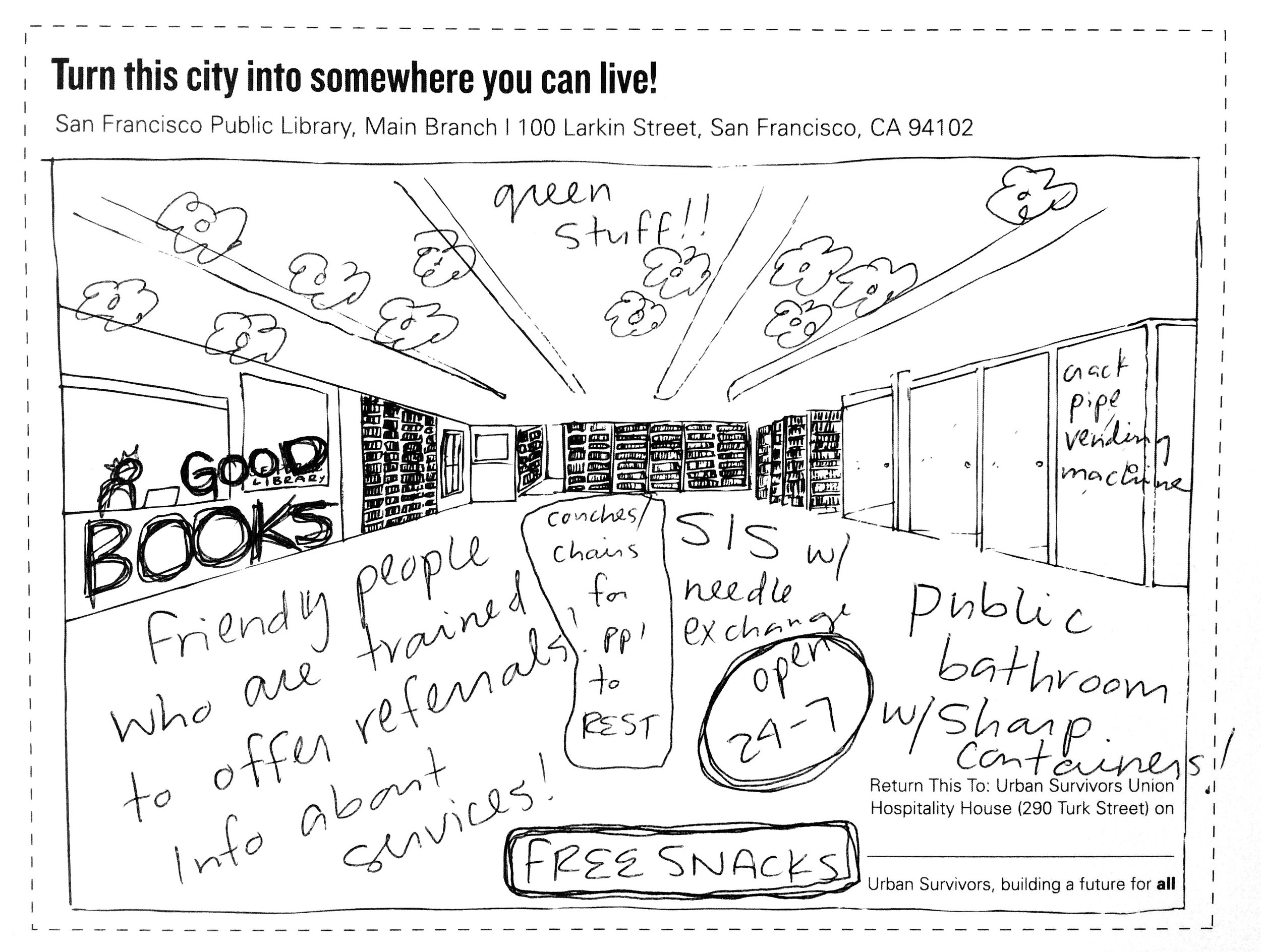

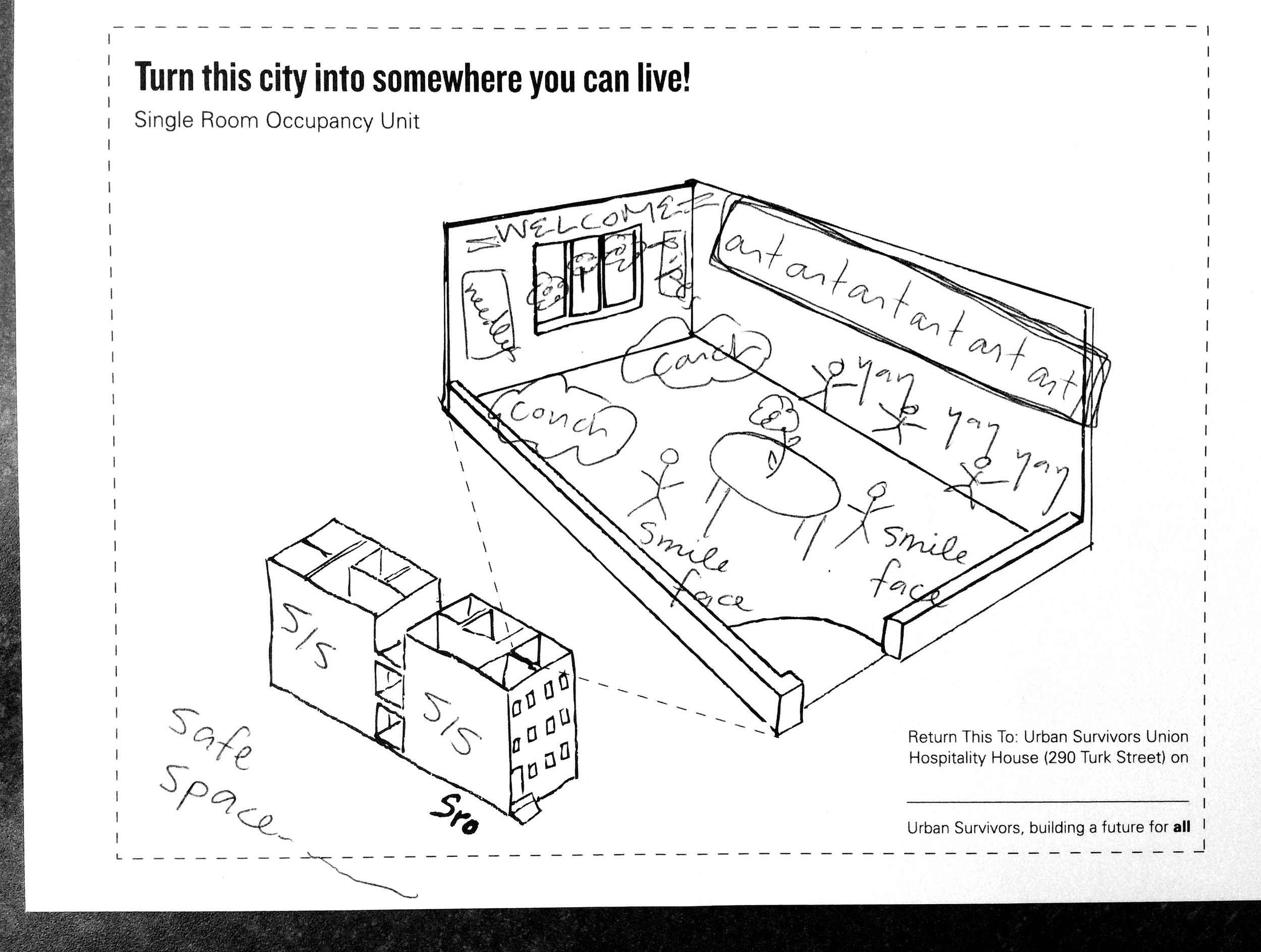

In the design process I realized that there was no consensus within the USU members about their mission. Engaging with that insight and using coloring books as inspiration, I designed a DIY flyer where filling in information by hand, created space for member's interpretation of the organization; it also became a shared team activity. The last page of the flyer was a tear out where USU users could re-imagine public spaces by drawing or writing their ideas and submitting them back to the USU.

““Putting together the kits and filling out the flyers became like a ritual for us.””

““I enjoyed thinking about re-designing the library...yeah, I’m there often and there are a lot of stupid rules they need to drop!”

Example of a submission made for a more safe and inclusive public library by a housing unstable resident of S.F.

project learnings

- This was some of the most personally challenging and humbling work I've done. I had to overcome my own ignorance & prejudices, remain empathetic, and present opportunities to return power back to individuals who felt stripped of it.

- I learned that the speculative design process opens up a space for dialogue on difficult issues—it's presents a platform for marginalized communities to articulate their concerns in an actionable format.

- I practiced adaptability as issues and insights arose in the design process, I embraced them and course corrected.